Reading is integral to our daily lives, serving various purposes ranging from relaxation to in-depth learning. How we approach reading often depends on our objectives — whether we are unwinding with a novel, seeking specific information, or engaging with academic texts.

Reading for Leisure

Reading for leisure is an unhurried journey through stories, ideas, and emotions. It allows us to experience pleasure, relaxation, and sometimes escapism through the written or spoken word. The motivation is personal enjoyment rather than academic, professional, or life admin obligations. Importantly, it allows the mind to wander and reflect in an unstructured manner.

Reading for Information

This type of reading is ideal for staying updated with current events, understanding the basics of a topic, or gathering data from multiple sources. Unlike leisure reading, the primary focus here is breadth and relevance, as depth is often secondary to efficiency.

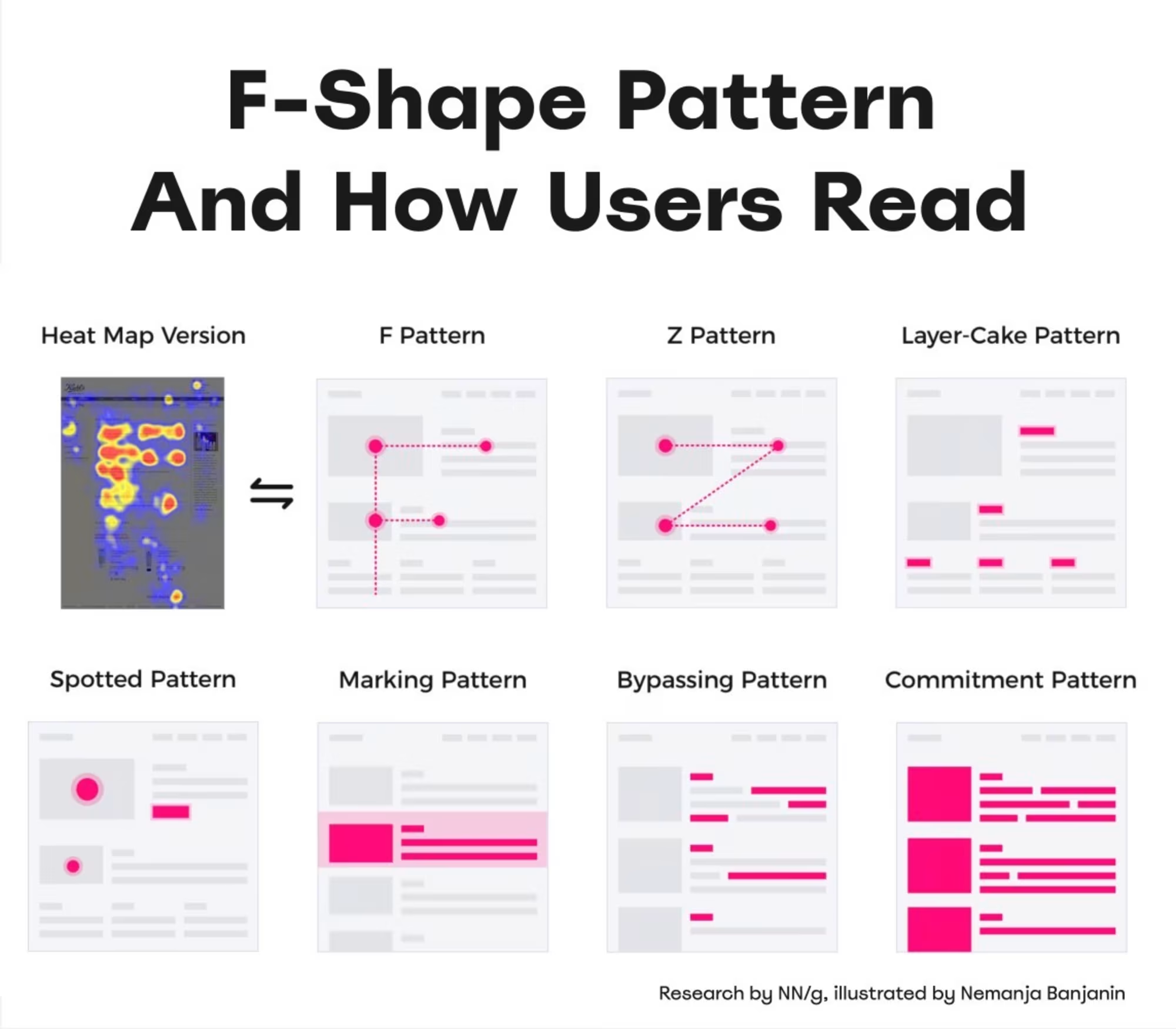

One common technique in this context is skimming, where readers quickly navigate a text to identify its main ideas without reading every word. The goal is to grasp central concepts by focusing on headings, subheadings, and key transitions. Words like “because,” “therefore,” and “consequently” indicate relationships between ideas, while terms like “however,” “but,” or “on the other hand” often introduce contrasts. This structured approach helps readers assess whether a more detailed reading is necessary.

Another technique, scanning, is employed when searching for specific information. Rather than absorbing the entire text, the reader moves rapidly through it to locate keywords or phrases that answer specific questions. Once a keyword is located, we read the surrounding sentences to extract the relevant information.

Different scanning patterns. Image credit: Nemanja Banjanin

We often encounter bloated books that struggle to maintain our interest, as humorously captured in a Goodreads review, haiku-style:

It’s overwritten

Yet still somehow underdone,

I only read half 🙁

That is why skimming and scanning are so valuable: they are essential for managing large volumes of information efficiently, especially nowadays, when we have access to more facts at our fingertips than we could absorb in a lifetime.

While quick reading techniques can save time, they may result in a superficial understanding of the material if used excessively. In some cases, particularly with complex or meaningful texts, a more thoughtful and deliberate approach is necessary to grasp the content.

Reading for Study

Reading for study is a deliberate, focused activity that requires deep engagement with complex material. Unlike information-based reading, which casts a wide net, study reading involves a narrow, intense light on specific areas. It demands critical thinking, reflection, and the ability to synthesize information.

We must become what Patrick Rael, author of Reading, Writing, and Researching for History, calls a “predatory reader.” This type of reader is adept at quickly identifying the most important parts of a scholarly text: the problem, the solution, and the evidence.

Reading scholarly material requires a new set of skills. You simply cannot read scholarly material as if it were pleasure reading and expect to comprehend it satisfactorily. Yet neither do you have the time to read every sentence over and over again. Instead, you must become what one author calls a “predatory” reader. That is, you must learn to quickly determine the important parts of the scholarly material you read. The most important thing to understand about a piece of scholarly writing is its argument. Arguments have three components: the problem, the solution, and the evidence.

Patrick Rael, Reading, Writing, and Researching for History: A Guide for College Students (Brunswick, ME: Bowdoin College, 2004)

Active reading is one of the most effective ways to absorb study material fully. This approach encourages us to question, annotate, and engage with the text as we read. Umberto Eco offers practical advice to enhance our active reading:

If the book is yours and it does not have antiquarian value, do not hesitate to annotate it. Do not trust those who say that you must respect books. You respect books by using them, not leaving them alone.

Umberto Eco – How to Write a Thesis

One highly effective strategy for study reading is the SQ3R method —Survey, Question, Read, Recite, and Review. This method transforms reading from a passive to an active process, enhancing comprehension and retention:

- Survey the text by skimming headings, subheadings, and summaries to get an overview of its structure.

A textbook is not an Agatha Christie murder mystery: you can look ahead.

In fact, you should look ahead.

Butte College – CHOOSING A READING STRATEGY

- Ask Questions based on the survey findings

- Read the material thoroughly, actively searching for answers to your questions.

- Recite the main points in your own words, either aloud or in writing, reinforcing understanding.

There are many things that I do not know because I photocopied a text and then relaxed as if I had read it.

Umberto Eco – How to Write a Thesis

- Finally, Review the material by revisiting your notes and summaries to solidify the knowledge in your mind.

Reading can sometimes be more than just collecting information because we transform words and facts into knowledge when we personalize and apply that information in meaningful contexts.

Information can be taken from books or teachers. But that also means it can be found with a quick Google search or a friendly email, so we don’t need to store it in our personal systems. Knowledge, though, is information that has been personalized. We gain knowledge when we understand information within personal contexts and make it relevant to our own interests, work, and existing knowledges.

morganeua – Note-Taking is Not Enough: Knowledge Management for Researchers and Writers

But many genres blur these reading boundaries, offering layers upon layers of storytelling, poetry, philosophy, science, and other facts. And so, perhaps the lines between reading for leisure, information, and study are more fluid than we realize. Maybe the best books are those where we feel like we are in a candy shop in the middle of an art gallery, in the center of a cinema, somewhere in a library hidden in a forest on an unknown island. Repeat ad infinitum, as each skin of a thought is perceived differently not only by different people but also by the us of today and the us of yesteryear.

On a personal note, I find that Olga Tokarczuk’s books, Flights and House of Day, House of Night, embody a symbiosis of all three reading styles — leisure, information, and study. What started initially as a leisure reading turned into rereading sessions and multiple Wikipedia tabs to grab all the tiny dewdrops glistening on words. Tokarczuk’s exploration of non-linear timelines and fragmented, interconnected essays, as she puts it, involves “gathering up all the tiny pieces and attempting to stick them together to create a universal whole.” Similarly, we synthesize all the tiny pieces of new information into coherent knowledge, much like building a puzzle of understanding.

All my life I’ve been fascinated by the systems of mutual connections and influences of which we are generally unaware, but which we discover by chance, as surprising coincidences or convergences of fate, all those bridges, nuts, bolts, welded joints and connectors that I followed in Flights. I’m fascinated by associating facts, and by searching for order. At base―as I am convinced―the writer’s mind is a synthetic mind that doggedly gathers up all the tiny pieces in an attempt to stick them together again to create a universal whole.

Olga Tokarczuk – The Nobel Laureate in Literature 2018 Acceptance Speech

Related Articles:

Letters to my Daughter: Learning How to Pass a Test

Mastering a Crucial Skill for Adaptation: Learning How to Learn

Of interest: Distributed practice and self-testing are highly effective strategies for transferring information into long-term memory. Combined with chunking (breaking down complex information into manageable parts), the Pomodoro technique, and alternating between focused and diffuse modes, these methods can be particularly useful when targeting study reading.